Simulations & Small Group Work

- Sara Bailey

- May 4, 2022

- 4 min read

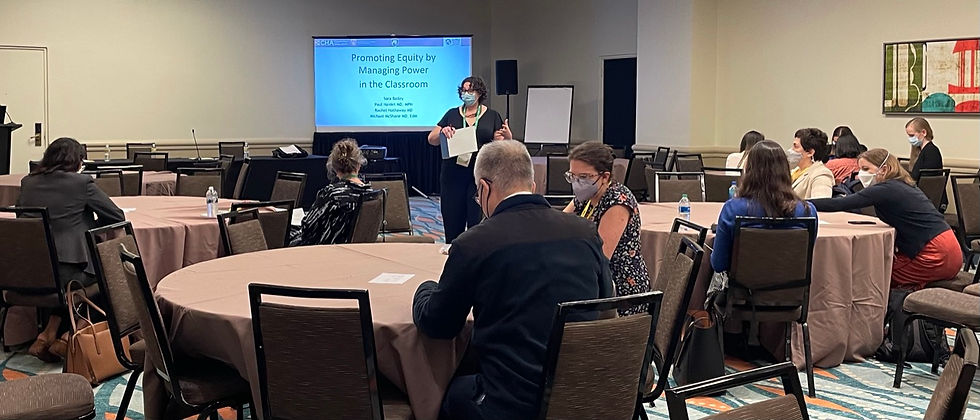

Since leaving the classroom, I haven’t had many opportunities to teach in a formal way, so I was excited to co-present two different workshops at a conference in early April. The two workshops couldn’t have felt more different for me as a presenter: in one, we were taking participants through the kinds of moves you can make as a teacher when a student is behaving or reacting in an unexpected way; in the other, we role-played how teachers use control and power in the classroom. While I had very different experiences from planning to presenting, I want to focus a little time reflecting on the experience of doing these sessions.

In the session geared toward helping manage unexpected student reactions, we had a lot of clarity about who would be covering which part of the content. There was an introduction, content sharing, small group work (which asked participants to wrestle with situations and apply a combination of the content with their own experience), and a whole group debrief. We’d practiced this several times, which meant that we had a good handle on how the session would flow, and we’d thought about how to pivot depending on things like how many people showed up to do the work. My part was to set up the small group work and then facilitate the whole group reflection. The session went off without a hitch; we moved from section to section and focused the reflection on the issues that participants found trickiest in the scenarios we gave them to work through. We shared ideas and perspectives, and folks walked away saying the information was helpful.

I wrote about my experience of practicing the session about power in the blog a few weeks ago, and it made me very nervous to role-play my part (an attending physician who needed to have a very high level of control in her classroom of residents). Before the session began, my co-presenters and I talked about what we would do if only three or four people showed up; we decided that wouldn’t be enough to run the role-play, and we’d have to convert to a discussion-based session, instead. I then moved to the hallway and tried to will the universe to only bring three people into our room. It didn’t work. Instead, twelve people joined us, sitting around three tables and waiting to begin. One of the other presenters warned the participants that they might feel uncomfortable at times, but she encouraged them to stick with it. Then, I hurriedly approached the front of the room, told everyone I was double-booked, and gave them seven minutes to discuss and choose a topic related to power in the classroom. I brought them back together after that time had elapsed, and the following three minutes were the source of my dread. I knew I had to go from table to table, hovering over people, cold-calling them for their answers, and then telling them their thinking was wrong before abruptly moving on. I went to the first table, chose someone, cut them off, told someone else at the table to help, and then also shot that person down. I moved to the second table, and the woman I demanded answer my questions looked at me and said, “I understand what you’re doing, and it’s making me uncomfortable.” I replied, “I’m glad you’re uncomfortable, and you still need to answer.” In that moment, I felt a huge sense of relief; someone had started to understand that I was intentionally acting in a particular way. My stress evaporated, and I felt much more comfortable continuing with my role. When I got to the third table, the woman I selected physically stood up and told me I wasn’t going to intimidate her. I called her by her first name, made a belittling comment about her thinking, and ended my section of the role-play. The next presenter began facilitating in a way that empowered the participants to share what they’d been feeling.

When the final presenter began the debrief of what these two very different models of power and control in a classroom highlighted, I was eager to jump back into the conversation (a stark difference from our practice round). The group’s observations and insights were thoughtful. One doctor reflected about how she believed she saw herself in how I maneuvered the room, and her humility opened the group up to diving in even further. At the end, the participants shared that the session had been transformative.

As an instructor, I got to experience two very different kinds of teaching and learning, back-to-back, and I’m really struck by the differences. Both took lots of planning and effort, both were about important topics, and both helped participants learn. But, if I’m being honest, one made the presenters do more work and the other asked the participants to do it.

In our more conventional session about managing unexpected reactions, we walked participants through much of the learning. We’d wrestled with what exactly to present and how to present it, divvying up speaker time. We had a conclusion that we wanted participants to walk away with. While I think it’s an important takeaway, as teachers, we’d already decided exactly what their learning should be. In the simulation about power and control, we had big ideas and some hopes for our participants’ learning, but we didn’t know where we would land. I think that’s what made it so satisfying when those learners made meaning that was personal and relevant to their own contexts.

Teaching and learning is difficult work. It requires so much of everyone involved, and I believe that teachers sometimes make the mistake of plotting out too much to make sure our students get exactly where we want them to be. But learning isn’t linear, and there’s no point when we’re done. I know that it’s the final stretch of this school year, but for any teacher reading, I encourage you to think about how you can release a little more work into the hands of your students. How can you set up an opportunity for them to learn something without deciding exactly what that something will be?

If you’d like help, send us a message here or through our Facebook page, and make sure to Follow us to see more of our content.

Comments